Network sovereignties are at least four different concepts in one category

By Vitalik Buterin, Ethereum

Over the last few years, there has been a lot of interest in a collection of topics around intentionally creating new cities and countries. On the more “normal” end, this includes projects like Culdesac, a newly built car-free neighborhood on the outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona. On the more “ambitious” end, we see Prospera, an autonomous zone inside Honduras that is already home to biotech startups selling novel treatments that are not yet available in the US.

And we also see everything in between. A few years ago, political philosopher Samo Burja asked why we were not building monasteries for software developers. Now, there is a prototype of such a thing running for six weeks in the spring of 2024 in Argentina. Mu, located in Chiang Mai last year and Buenos Aires this year, can be described in many ways, one of which is to call it a semi-decentralized nomad university. Minerva takes the “nomad university” concept further. Montelibero is an in-person “society based on individual freedom” in Montenegro founded by Russian exiles. California Forever aims to create a large-scale new city in California, using the opportunity to do things “from scratch” to introduce better urbanism and policy. My own contributions to this space are twofold: two years ago, I reviewed Balaji Srinivasan’s magnum opus on the idea of communities forming in the cloud and then materializing on land as “network states”, and last year, I created Zuzalu, my own two-month-long popup experiment in the genre to try to generate better understanding of what could realistically be done with these ideas.

Projects like this are the subject of Primavera di Filippi’s article “New Network Sovereignties: The Rise of Non-Territorial states?”, which kicks off this series. Primavera correctly identifies that we are dealing with a new class of collective human actor, one that is not in the same category as a traditional sovereign state, but is sufficiently capable of exercising collective autonomy and choice that it is not absurd to use the word “sovereign” to describe it. My purpose in writing this post, and listing the diverse range of projects above, is to show that what we are talking about is a surprisingly large design space. The projects above share many common threads, but they serve a wide variety of goals and values. These projects have very different profiles in terms of what they intend to do, what kinds of people they serve, and what they demand out of the host countries that they locate themselves in. The fundamental “thesis” for why it might make sense for each of these to exist is different in each case.

To show these differences in more detail, let us first explore four major “theses” for why creating or participating in a “network sovereignty” might make sense.

Thesis 1: the free city-state

The “free cities” discourse, as I remember it from ten to twenty years ago, revolved around a simple pitch: we can build new cities, which could either be sovereign countries (eg. through seasteading) or zones within existing countries that negotiate for some level of autonomy or exemption from certain classes of regulations. Prospera has this level of autonomy, and takes advantage of it to institute an entire novel legal framework. In many cases, this framework allows people and businesses to be regulated under the law of a major existing country of their choice – or sometimes even avoid such regulation entirely if they instead buy liability insurance.

In practice, the clearest immediate beneficiary of this approach is often biotech: Prospera is already home to biotech startups selling several kinds of novel treatments, eg. Minicircle. However, it could also apply to other sectors: natural candidates include blockchain/crypto projects and transportation (eg. drones).

- Who: entrepreneurs

- What they do: participate in innovative and highly unusual businesses

- What they need: legal autonomy or regulatory exemptions, infrastructure

Thesis 2: the satellite town

Many existing cities around the world have dysfunctional policies and infrastructure. At the same time, they have powerful network effects: they might be the centers of large tech industries, financial hubs, or the capitals of their countries, and they have airports with many direct connections to other important hubs. Often, there is a large amount of relatively unused land fifty kilometers away from the city – in the ideal case (eg. as with Culdesac), on the other side of the airport.

So why not… build a new small town in some of that land? As anyone who has visited a ski town (or a surf town, or Longyearbyen) knows, you only need a relatively small population of around one to five thousand to be able to sustain a large variety of modern amenities. In such a tokwn,people and families would pay much cheaper rent, enjoy better, more pleasant and walkable urban design, and still have a large-scale city and airport easily available to them.

- Who: regular, often middle to upper middle class, individuals and families

- What they do: remote work

- What they need: affordable cost, good urbanism, proximity to major cities

Thesis 3: exiles

2022 and 2023 have been traumatic years for large numbers of people around the world for reasons that largely have to do with worsening economies and worsening geopolitics. Authoritarian regimes appear to be breaking implied social contracts of “you don’t mess with our politics and we won’t mess with your personal life” and increasingly intruding on cherished personal freedoms and even human life. At the same time, economies in many parts of the world have been increasingly sluggish. One very natural response under these conditions is to leave: get yourself and your family to safety, stop contributing to the machine, and then either lead a peaceful live in your new home, or build strength to slowly nurture a competing economic and political vision that might eventually lead to reform in the country you left.

But people in this position often face a challenge: they have a hard time thriving in their new home. Sometimes this takes the form of racism, anti-foreign bias and even institutional hostility, but other times the issue is simply loneliness and difficulty breaking into the local economy and society. These are tough problems. But they are problems that a group of hundreds of people migrating to the same place together, and supporting each other online and offline, can plausibly handle much better than one person working alone.

- Who: people escaping other countries

- What they do: everything

- What they need: to be allowed to come in the first place (visas), to be welcomed

Thesis 4: nomads

A growing number of people see themselves as location-independent: they work remotely, have social lives at least in part remotely, and change their locations with varying frequencies. This can often be a great way to save money, while at the same time learning about the world and different people and cultures.

However, people in this position can easily end up missing the benefits of in-person communities that have shared interests that they care about. There is a reason why the “drop out of college” enthusiasm of 15 years ago has been much less successful so far than predicted: learning and staying motivated are fundamentally social, and it’s just much easier to do those things in a dedicated environment surrounded by fellow students and teachers. People who are working face a similar challenge: after all, in a modern economy, you can never afford to stop learning. “Popup villages” dedicated to specific topics, whether permanent or temporary, could help people fill this need.

- Who: mostly young people

- What they do: working, learning

- What they need: a social environment with people with similar interests

What will the relationships between these communities and existing countries look like?

There are plenty of “theses” that go beyond the above four, but they are a good starting point because they cover a wide range of potential participants: the young and the established, the power users and the powerless, single people and families. There is a large number of commonalities between these theses, but there is also a large number of differences. One important topic in Primavera’s opening article is that these new communities will have relationships with host countries that are complex, and are not purely competitive. But what might the details of these relationships actually look like, and what are some possibilities – both benefits and risks – that they offer? Here, we need to look more deeply and the similarities and differences between the above cases.

First, the commonality. All four of the above categories have existed for centuries: “free city” proponents often use early Hong Kong and Shenzhen as examples, centrally planned satellite towns have existed for a long time and Irvine is a good example of a recent example within California itself, emigrants have often aggregated in specific districts in their new homes, and Kevin Kelly has written at length about the long tradition of nomads in Mongolia. What is new, however, is much more powerful possibilities for coordination due to digital technology. This includes communication technology (internet, group chats…), but also potentially “trust technology” of the type that many readers of this article may be particularly familiar with: online reputation, blockchains, zero knowledge proofs, smart contracts, digital voting…

This new and more powerful coordination technology makes it much more possible than before to create and adjust new network effects intentionally. Rather than accepting the dominance of existing hubs as a fait accompli, groups could collectively choose to set up new hubs de novo, each member initially relying on the promises of the others to go to the same place at around the same time. And if a given destination initially looks promising, but ends up unfavorable or abusive, collective choice to enter can turn into collective choice to leave. In ages past, this would generally be possible through a single central charismatic leader. With modern communication technology, something much more democratic – perhaps a design inspired by assurance contracts in which a person gives a list of options that are agreeable to them and commits to join any one of them if enough other people do – also becomes a possibility.

This collective decision-making power also creates collective bargaining power, allowing communities to negotiate for agreements that would be much more difficult to accomplish if they acted alone. This can often even be to host countries’ benefit: a common complaint of tourists is that they clamp up in a few high profile venues (eg. Bali, Venice) and over-exploit some regions; communities with decision-making power could intentionally make deals to be “counter-cyclical”, locating themselves to maximize positive impact and minimize negative impact.

Now, the differences. The largest question in the relationship between these new communities and their host countries is what kind of legal autonomy they require. Ten to twenty years ago, the discourse focused heavily on getting as much autonomy as possible: ideally outright sovereignty, and failing that full autonomy in everything but foreign policy. This reflected ideological purism that was stronger in libertarian movements at the time. What people discovered, however, is that it is very difficult to convince a country to give that much up. And so what we are seeing a move toward a pragmatic approach of “get the specific kind of autonomy you need for your specific goals”.

“The free city-state” is the most ambitious out of the above four from a legal perspective, and so it is the one that carries the most risk for host countries. I would argue that the greatest risk to host countries is one that is talked about relatively little: reputational and diplomatic risk. If a country gives a free city-state autonomy, and that free city-state starts doing things that lots of people in the host country dislike, that will harm the ruling party’s political position. If it starts doing things that elites in other countries dislike, that will harm the country’s reputation, reduce enthusiasm for including them in defense or trade alliances that are beneficial for the country’s broader population, and in extreme cases lead to greater types of isolation. One concern that I predict host countries will have is, the risk that a community comes to them asking for autonomy, marketing themselves as doing something mild, but then ends up doing something else over time. The most practical way to mitigate the risks is to establish clear rules ahead of time that match both sides’ expectations.

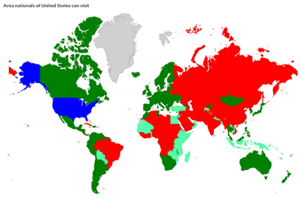

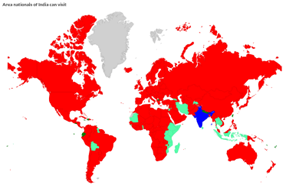

The other three groups seem like they require relatively few legal asks from the host country, and the asks that exist may well be at the local level rather than the federal level (eg. zoning exemptions). However, it is worth zooming in on one particular ask that exiles and nomads require: visa issuance. This is a topic that citizens of rich countries, even those that consider themselves social-justice minded, frequently neglect to consider: citizens of rich countries can easily go to almost everywhere they want to go, usually without a visa, but citizens of poor countries are often locked out from much of the world.

Top: where Americans can easily go. Bottom: where Indians can easily go.

It is my belief that visa and immigration restrictions are the single category of government regulation that causes the most concrete harm to people today. At the same time, many countries are in the middle of various refugee crises, and it is a (to me, quite unfortunate) fact that political appetite for letting more people come into Western countries in the 2020s is quite low. Network sovereignties, however, give us a fascinating new lever to try to improve things in this regard. Often, a large factor motivating skepticism of immigration is concern about the quality of the immigrants: will they contribute productively to the economy, or will they commit crimes? If they come as a tourist, are they likely to overstay? Are they a good culture fit?

The idea that I propose is for many types of network sovereignties to seek autonomy from host country governments in one specific area: immigration. Instead of each person applying individually, a network sovereignty can apply for a fixed number of slots. A network sovereignty is a relatively large actor with a publicly visible reputation, and so governments could evaluate the villages for quality, saving both them and the individual members costs. From a host country’s perspective, someone from a low-income country who is a member of a network sovereignty that has been well-vetted is plausibly lower risk than someone from a medium-income country whom they would let in without a visa already.

While such negotiations are not yet standardized enough to be easy to participate in, the other thing that these communities can do is simply choose to locate themselves in countries that make it easy for people from around the world to come. The number of these countries is increasing, eg. recently Kenya replaced their visa requirement for arrivals with a much simpler electronic travel authorization system.

There are other forms of autonomy that are valuable. One area is personal freedoms: LGBT rights are a common issue, and depending on the type of community, freedom of speech, freedom to use certain substances, freedom to use cryptocurrency might also come up. Often, conservative countries have an unspoken policy that foreigners are mostly not bothered if they do these things, but only if they do them quietly. This “sort of works” for tourists, but communities need a higher level of stability. Communities are also inherently more prominent, and a community continuing to exist carries a higher implied level of legitimacy than quiet individual activity being tolerated, so this can lead to political friction. This area is complex, and will need to be negotiated over time.

Conclusions

What we see in the movements that I have talked about in this article are some important commonalities, most notably the benefits that they receive from acting as a community rather than separate individuals, and new technologies that supercharge their ability to do so, but also important differences in their goals, and in their relationships with host countries.

For these reasons, it is important to avoid a “one size fits all” approach to thinking about them: different groups have different needs, and a biotech hub will have a completely different profile from a software developer monastery or a decentralized university. At the same time, it is worth starting to think about standardizing certain categories that are valuable to particular groups, because even though groups can engage in custom negotiations, many still lack sophistication and do not know how to even start doing such a thing. “Digital nomad visas” being increasingly offered to individuals are one example of this. In our case here, the key idea is that there is a relationship being created between a country and a group. Legal structures to represent groups have of course existed for centuries, but they seem to be far too inadequate to deal with the issues here. These are not new countries, but they are new something – in fact, several different new somethings. And it’s worth starting to think how to productively engage with this category.

Vitalik Buterin is a co-founder of Ethereum. In 2022, he authored Proof of Stake: The Making of Ethereum and the Philosophy of Blockchains. His website is https://vitalik.eth.limo/.